The Lords' Blockade: Britain's Assisted Dying Standoff in 2026

A Warning from the Upper Chamber

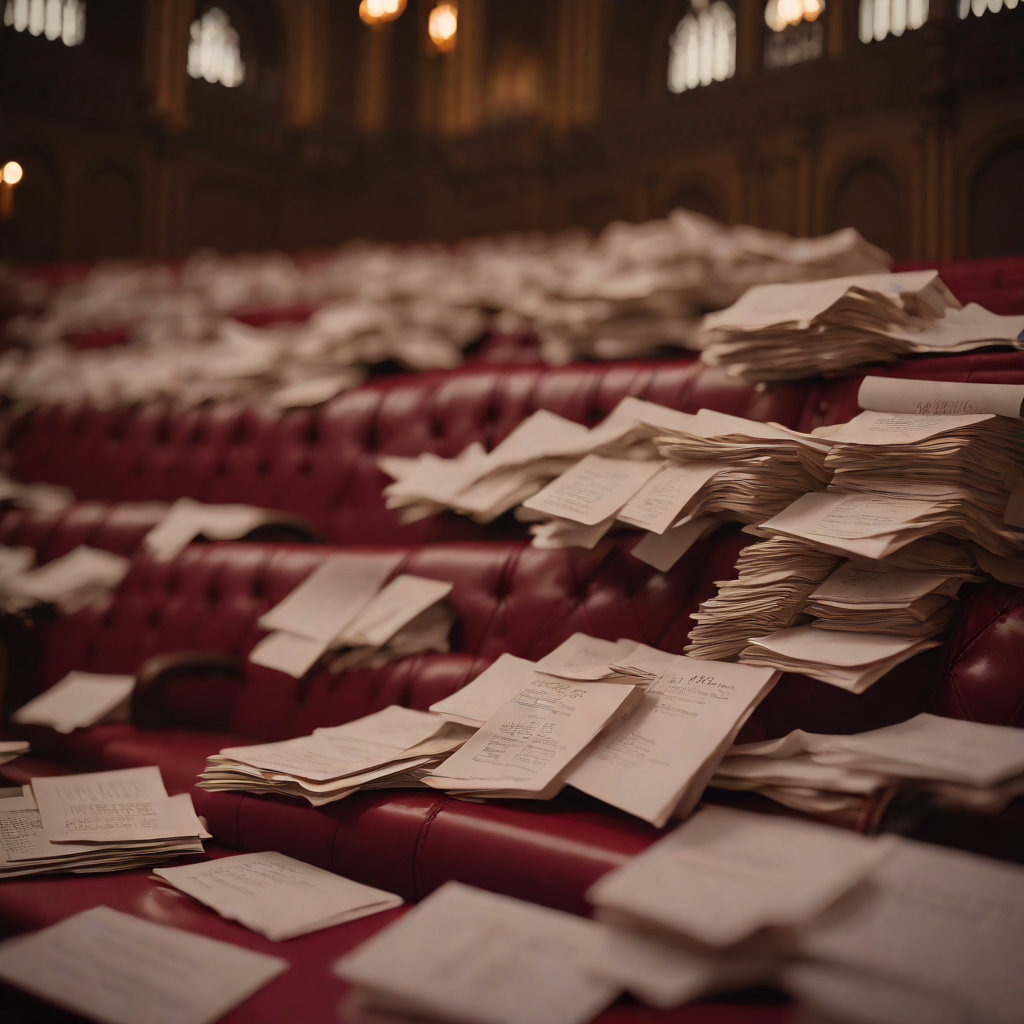

The warning came not with a bang, but with the rustle of paper—specifically, the sound of 1,100 separate amendments being tabled in the House of Lords. Earlier this week, Lord Falconer described the scene as "parliamentary trench warfare." Standing before a thinning chamber, the veteran Labour peer and former Lord Chancellor issued a stark ultimatum: the Upper House risks becoming the "graveyard of public will" if it continues to exploit procedural loopholes to suffocate legislation that has already cleared the elected Commons. His concern centers on a cadre of opponents who have effectively weaponized the Lords' lack of a strict guillotine motion—a mechanism used in the Commons to limit debate time—allowing a minority to filibuster the Assisted Dying Bill into oblivion simply by talking until the parliamentary clock runs out in May.

This stalemate exposes a fundamental fragility in the British constitutional model that American observers might find baffling. In the United States, moral legislation is typically stress-tested in the "laboratories of democracy"—individual states like Oregon or Washington—where voters or local legislatures can enact reforms without requiring a federal consensus. If a law fails in Oregon, it does not paralyze the machinery of Washington, D.C. Yet in Westminster, a single procedural bottleneck in an unelected chamber can veto a policy supported by 75% of the British public. As James Carter, a comparative constitutional scholar at Georgetown, notes, "The US system creates containment zones for controversial policy experiments; the UK system creates a single point of failure. You are watching a 19th-century deliberative body try to process a 21st-century bioethical crisis using rules written before the telephone."

The friction is palpable. While opponents argue that the deluge of amendments is a necessary safeguard against a "slippery slope," the sheer volume—two-thirds of which were tabled by fewer than a dozen peers—suggests a strategy of attrition rather than scrutiny. With the Trump administration currently accelerating deregulation across the Atlantic, the contrast is sharpening: while the US prioritizes speed and state-level autonomy, the UK remains bound by a centralized, ceremonial deliberation that prioritizes consensus over action. For the thousands of terminally ill Britons waiting for legal clarity, this is not just a constitutional quirk; it is a denial of time they do not have.

The Anatomy of Resistance

To an American observer accustomed to the patchwork efficiency of federalism—where Oregonian voters authorized the Death with Dignity Act nearly three decades ago while Alabama remains steadfastly opposed—the legislative paralysis currently gripping London offers a sharp lesson in the perils of centralized morality. The blockade is not occurring in the elected House of Commons, which ostensibly reflects the shifting public will, but in the House of Lords. This unelected upper chamber has become the fortress of resistance, deploying a strategy that is less about direct negation and more about procedural asphyxiation. Unlike the US Senate, where a filibuster is a blunt instrument of obstruction, the Lords' resistance is surgical, conducted through what parliamentary scholars call "wrecking amendments"—proposals ostensibly designed to improve safety but practically engineered to make the law unworkable.

The composition of this resistance is alien to the secular separation of church and state enshrined in the US Constitution. The "Lords Spiritual"—26 bishops of the Church of England who sit by right in the legislature—form a voting bloc that has no parallel in Washington. While religious lobbies in the US must exert influence from the outside via Super PACs and grassroots pressure, the Church of England exerts its influence from the red benches of the legislative chamber itself. James Carter, monitoring the proceedings from New York, notes that while US resistance is often framed around constitutional rights or federal overreach, the Lords' opposition is rooted in a paternalistic protectiveness that overrides polling data. "In the US, if a state legislature blocks a bill, the voters can often introduce a ballot initiative," Carter observes. "In the UK, there is no workaround for the Lords except the Parliament Act, a nuclear option that takes years to trigger."

However, attributing the stall solely to theology would be a reductionist error. The most formidable barrier comes not from the pulpit, but from the clinic. The "Medical Peers"—senior doctors and surgeons elevated to the peerage—have formed a technocratic wall against the bill. They argue that the US model, particularly the systems in Washington State and California, lacks sufficient safeguards against coercion. Citing a 2025 expansive study from the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, opponents in the Lords have flooded the committee stage with demands for judicial oversight in every single case. This requirement would mandate that a High Court judge, not just two doctors (as is the standard in Oregon), sign off on every assisted death. Proponents argue this would create a legal bottleneck effectively banning the practice for all but the wealthy and litigious, echoing the "access gap" criticisms often leveled at the US healthcare system.

The Atlantic Divide

While the halls of Westminster echo with high-minded philosophical debate, the procedural reality on the ground tells a story of two distinct democratic metabolisms. The current paralysis in London is not merely a political accident but a structural feature of the Westminster model, where a single choke point in the House of Lords can effectively veto the will of the Commons. Across the Atlantic, the United States offers a stark counter-narrative: a chaotic but functional "laboratory of democracy" where the stalling of federal consensus does not equate to the paralysis of individual rights.

In the United Kingdom, the "Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill" faces what constitutional scholars at the University College London describe as "attrition by amendment." Despite securing a majority in the elected House of Commons, the legislation has languished in the Upper House, where unelected peers have tabled over 400 amendments since the start of the 2026 session. This centralized deadlock means that for a British citizen, the right to choose is a binary, nationwide switch—currently stuck in the "off" position. There is no alternative jurisdiction, no neighboring county with different rules; the blockade is total.

Contrast this with the American experience under the second Trump administration. While the federal government remains largely disengaged from the Medical Aid in Dying (MAID) debate—viewing it through the lens of states' rights—the movement at the state level has continued to accelerate. The US system treats moral legislation not as a monolith but as a market of jurisdictions. When the New York legislature stalled on its own Medical Aid in Dying Act earlier this year, proponents didn't face a national dead end. Instead, attention shifted to Maryland and Minnesota, where similar bills advanced through committees with renewed momentum.

This "Atlantic Divide" creates a fundamentally different user experience for the terminally ill. For Sarah Miller, a 58-year-old former architect diagnosed with ALS, the fragmented US system offered a lifeline that a centralized system could not. Living in Texas, where assisting a suicide remains a felony, Miller faced a prognosis of agonizing decline. However, unlike her British counterparts who must navigate the logistical and financial labyrinth of traveling to Switzerland, Miller simply exercised her rights as a US citizen to move. By establishing residency in Oregon—a process simplified by that state's removal of residency waiting periods in 2023—she accessed the autonomy she sought. "It wasn't easy to leave my home," Miller noted in a recent interview with the Death with Dignity National Center, "but the fact that a flight to Portland offered what a fight in Austin couldn't is the definition of American liberty."

Population with Legal Access to Assisted Dying (2026 Est.)

However, the American model is not without its critics. Opponents argue that the "postcode lottery" of rights creates a two-tier system of justice, where the wealthy, like Miller, can migrate to autonomy, while the poor remain trapped by the laws of their home state. Yet, from a legislative mechanics perspective, the US approach prevents the minority veto that currently hamstrings the UK. In Washington D.C., the Senate filibuster is a tool of obstruction, but in the realm of MAID, the silence of Congress has allowed the states to speak. In Westminster, the silence of the Lords has effectively silenced the nation.

The Safeguard Trap and the Export of Death

In the intricate dance of British parliamentary procedure, the "Safeguard Trap" has emerged as the most effective weapon for opponents of assisted dying reform. The argument is seductive in its prudence: if the state is to sanction the ending of a life, the mechanism must be flawless. Yet, as the calendar turns in 2026, it is becoming increasingly clear that the demand for perfection is serving as a de facto moratorium. The shadow looming over Westminster is not American, but Canadian. The rapid expansion of Canada's Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) program has provided British peers with a potent "slippery slope" narrative, allowing them to weaponize Canadian data to demand safeguards so stringent they threaten to render the British bill inoperable.

This systemic fragility creates a "trap." To assuage fears of a Canadian-style expansion, drafters of the UK bill have already included judicial oversight. Yet, during the committee stage, peers have tabled hundreds of amendments, some demanding psychiatric assessment for every applicant or extending waiting periods beyond the life expectancy of many patients. The result is a legislative paralysis unique to bicameral systems where the upper house possesses revisionary power but lacks democratic mandates.

Assisted Deaths as Percentage of Total Deaths (2025 Est.)

For wealthy Britons, the "right to die" has existed for decades—it is simply a purchasable export. While the House of Lords debates, a steady stream of terminally ill citizens continues to board flights to Zurich. This outsourcing of death effectively privatizes a public moral dilemma, creating a two-tier system where autonomy is a luxury good. In 2026, the average cost of an assisted death at organizations like Dignitas has surged to approximately £15,000 ($19,000), excluding travel and repatriation costs. This figure effectively bars the working class from accessing the same end-of-life choices available to the affluent.

The "export" model also creates a dangerous data vacuum. Because these deaths occur outside the jurisdiction of the NHS, British authorities lose the ability to monitor or regulate them. By forcing citizens to Switzerland, the state relinquishes its power to protect them at the very moment they are most vulnerable. The irony of the 2026 stalemate is that the UK is not preventing assisted dying; it is merely preventing regulated assisted dying on British soil.

Future of the Bill

The legislative paralysis currently gripping Westminster over the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill offers a vivid case study in the structural inefficiencies of centralized moral governance. The path forward has narrowed to three distinct, high-stakes trajectories. The most probable outcome is "death by amendment," where the bill is burdened with so many complex safeguards that it becomes administratively unworkable. If amendments render the bill toothless, the government faces a nuclear option: invoking the Parliament Act to bypass the Lords' veto. However, for Prime Minister Starmer's government, already navigating a fragile economy and international instability, spending precious political capital to force a divisive social issue through parliament may be a tactical bridge too far.

The third possibility is simply letting the clock run out. If the Lords can delay the bill until the end of the parliamentary session, it dies automatically. This vulnerability highlights a profound weakness in the British system: while the US creates policy through iterative, localized experimentation, the UK demands a consensus that its bicameral machinery is increasingly ill-equipped to deliver. The fate of the bill now rests less on the ethics of euthanasia and more on whether the Commons has the sheer endurance to outlast the Lords' filibuster.