Thwaites Glacier Vigil: The Human Cost of Verifying Doomsday

Seventy miles from the nearest solid rock, the concept of "ground" becomes a cruel abstraction. At Camp Ghost—a temporary cluster of swaying nylon and modified shipping containers perched on the Thwaites Eastern Ice Shelf—silence is the enemy. Silence means the wind has died down enough to hear the ice itself. It groans, a deep, resonant bass note that vibrates through the cot of Michael Vance (a pseudonym), a glaciologist on his third rotation.

"You don't sleep through it," Vance says, adjusting the straps of his thermal gear. "You lie there and calculate the frequency. High-pitched cracks are surface tension. The deep booms? That’s the shelf losing its grip on the seabed a mile below us."

This is life at the Zero Point. While policymakers in Washington debate the economic viability of green energy subsidies and the Trump administration scrutinizes the National Science Foundation’s polar budget, the team here is living on top of the most consequential geological question of the century. The Thwaites Glacier, roughly the size of Florida, is widely referred to as the "Doomsday Glacier" because of what it holds back: enough ice to raise global sea levels by two feet directly, and potentially ten feet if its collapse triggers a cascade across West Antarctica.

But satellites, for all their sophisticated radar interferometry, cannot see what is happening in the chaotic mix of saltwater and basal ice at the grounding line. To confirm the timeline of collapse, human beings must physically stand on the fracturing edge and drop sensors into the abyss.

The Physics of the Invisible

The physical toll of this vigil is absolute. The average temperature in January, the Antarctic summer, hovers at a deceptive -20°F, but wind chills can plummet to -60°F in minutes, turning a routine equipment check into a survival situation. The camp is transient by design. As the ice flows seaward at a rate of over a mile per year—accelerating noticeably since the early 2020s—the coordinates of "safe" ground shift daily. The team utilizes ground-penetrating radar every morning to map new crevasses that may have opened overnight between the sleeping quarters and the drill site.

The logistical tenuousness mirrors the data they are collecting. The "cork" in the bottle is disintegrating. In 2024, the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC) confirmed that warm seawater was infiltrating miles beneath the glacier, melting it from the bottom up. Now, in 2026, the on-site team is hunting for evidence of Marine Ice Cliff Instability (MICI), a theoretical mechanism where tall ice cliffs crumble under their own weight once the supporting shelf is gone. If the sensors Vance and his team are deploying—robots shaped like torpedoes known as Icefin—detect the specific salinity signatures indicative of rapid basal channel widening, the models for coastal inundation in Miami, New York, and Shanghai will need to be rewritten not for the next century, but for the next decade.

To understand why a team of glaciologists would risk their lives camping on a shifting ice shelf in the middle of the Antarctic winter, one must first understand the limitations of our eyes in the sky. Since the mid-1990s, satellite constellations like the European Space Agency’s Sentinel and NASA’s ICESat-2 have revolutionized our view of the poles. They track surface velocity and elevation changes with millimeter precision, beaming data to comfortable server rooms in Boulder and Cambridge. But these satellites suffer from a critical blindness: they cannot see through two miles of ice to the point where the glacier actually meets the rock.

This is the "grounding line"—or more accurately, the grounding zone—a chaotic, miles-wide hinge where the massive Thwaites Glacier lifts off the bedrock and begins to float as an ice shelf. It is here that the battle for the world’s coastlines is being fought, and it is a battle defined by hydrodynamics, not just thermodynamics.

Current models suggest that Circumpolar Deep Water—ocean currents warmer than the ice itself—is being channeled underneath the floating shelf, eating away at the glacier’s underbelly. This process, known as basal melting, creates vast cavities that satellites cannot detect until the surface inevitably collapses into them. As Dr. Pettit’s team confirmed during the 2025 field season, the reality below is far more turbulent than the smooth friction coefficients used in previous climate models. The interface isn't a flat slab melting evenly; it is a complex inverted landscape of terraces and upside-down canyons that accelerate the destruction.

The Retrograde Trap

The structural vulnerability of Thwaites lies in a geological quirk that glaciologists call a "retrograde bed." Unlike a mountain glacier that flows down a valley and eventually stabilizes, Thwaites sits in a bowl that gets deeper the further inland you go. The current grounding line rests on a subsea ridge. If warm water pushes the ice back past this ridge, the glacier will retreat down the slope into deeper water. Physics dictates that thicker ice flows faster. As the ice front retreats into the basin, the cliff face becomes taller and heavier, increasing the stress until the ice creates a self-sustaining feedback loop of collapse—a phenomenon known as Marine Ice Sheet Instability (MISI).

"You cannot model friction if you don't know the roughness of the rock," says David Chen (a pseudonym), a geophysicist who spent three months at the shear margin camp in late 2025. "Satellites give us the 'what' and the 'where,' but they don't give us the 'why.' For that, you need a seismometer on the ice, and you need a robot in the water."

Thwaites Flow Velocity vs. Grounding Line Retreat (2020-2026)

The Robot and the Drill

At the coordinates 75° South, 106° West, the silence of the Antarctic plateau is shattered not by the wind, but by the roar of industrial generators. The centerpiece of this operation is a marvel of brute-force engineering: a hot-water drill capable of melting a hole through nearly 2,000 feet of solid ice, creating a fleeting portal into the hidden ocean below.

For the team on the ground, the drill is a demanding beast that requires constant vigilance. It consumes thousands of gallons of aviation fuel, heating melted snow to near-boiling temperatures to bore a narrow shaft—barely wider than a dinner plate—straight down into the abyss. The technical challenge is immense. If the water pressure drops or the heaters fail, the hole can freeze shut in minutes, trapping whatever instruments are below and effectively ending the season’s research. Chen describes the process as "keeping a vein open in a body that wants to heal itself."

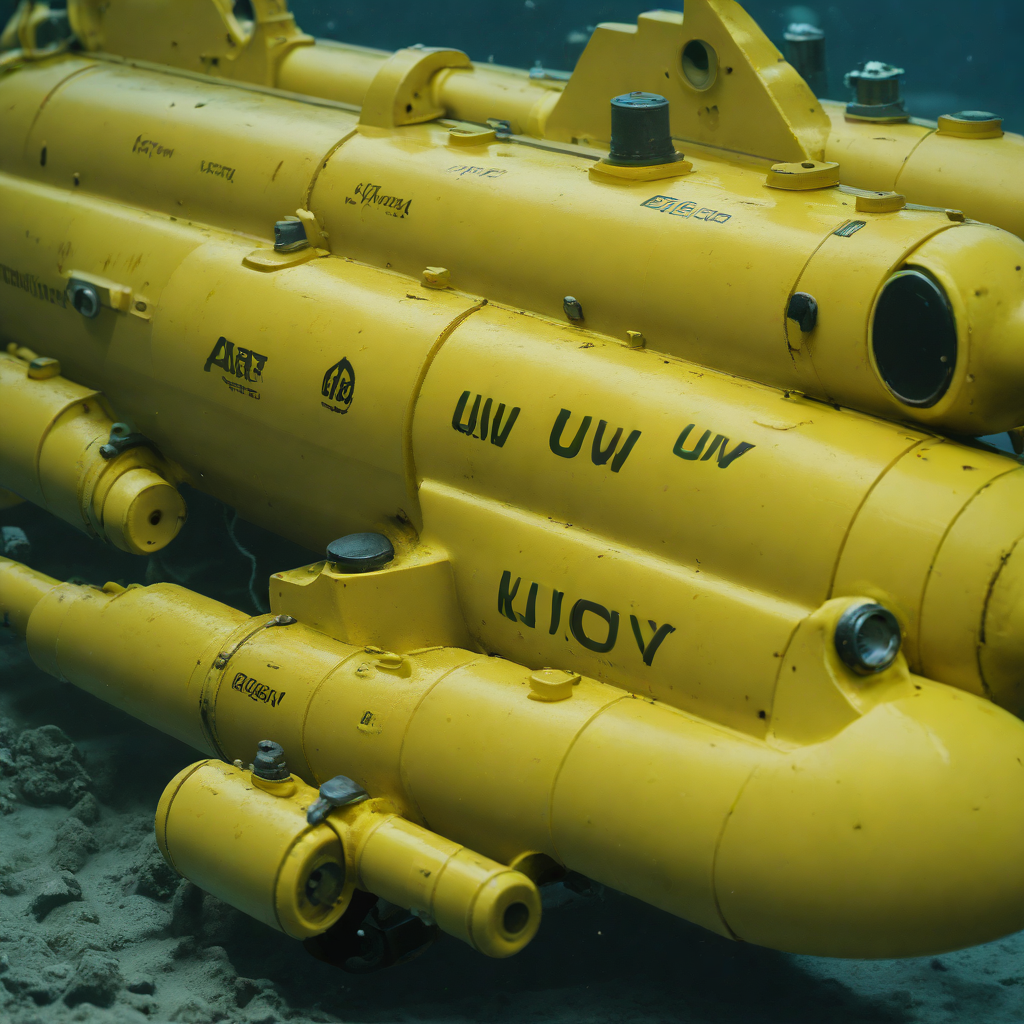

Once the breach is made, the focus shifts to the Icefin, a slender, yellow autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV). Lowered on a tether through the borehole, it acts as a remote sensor suite, swimming into the cavity beneath the floating ice shelf where the glacier meets the ocean—the critical "grounding line."

The data Icefin retrieves is terrifying in its clarity. It reveals that the ocean water circulating beneath the shelf is significantly warmer than the freezing point, eating away at the ice base like acid. The robot’s high-definition cameras and sonar have documented deep crevasses and "staircase" formations in the ice underside, structures that increase the surface area exposed to melting and accelerate the glacier's retreat. This is the ground truth that satellites orbiting hundreds of miles above cannot see.

Cracks in the Foundation

The silence of West Antarctica is a lie. For the thirty-two souls stationed at the remote field outpost on the Eastern Ice Shelf, the landscape is defined not by stillness, but by a violent, continuous groaning. It is a visceral, mechanical grinding that vibrates through the floorboards of the modular habitats, a constant reminder that the solid ground beneath them is actually a moving conveyor belt sliding into the Amundsen Sea.

For Chen, the reality of this instability became terrifyingly tangible just forty-eight hours ago. A routine sensor check turned into a survival situation when a hairline fracture he was monitoring suddenly expanded, splitting the ice with the force of a thunderclap. "It wasn't a slow drift," Chen explains. "It was instantaneous. One second I was standing on a flat sheet, the next there was a dark blue gash three feet wide running straight through where our comms tower stood."

The data Chen and his team are risking their lives to collect reveals that the ice shelf is not merely melting from the ocean's heat; it is mechanically shattering from internal stress. The on-site team has documented a phenomenon they are calling "cascading micro-fractures"—tiny, invisible webs of weakness that propagate miles ahead of the visible rifts. When these webs fail, they do so catastrophically and without warning.

Thwaites Structural Integrity: Model vs. Reality (Jan 2026)

The 65-Centimeter Reality

The wind on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet does not howl; it screams, a constant, physical assault that batters the nylon walls of the "Yellow Submarine"—the affectionate, if ironic, nickname for the mess tent at the Remote Camp. Here, 900 miles from the nearest permanent station, a team of glaciologists and engineers huddle around a diesel heater, their world reduced to the immediate radius of survival. They are not here for the scenery. They are here because of a single, terrifying number: sixty-five centimeters.

To a casual observer in a landlocked state, sixty-five centimeters—roughly two feet—might seem negligible. But for the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, this figure represents the potential global sea level rise held within this single, Florida-sized river of ice. In the context of the Trump administration's aggressive deregulation of coastal protections and the renewed energy policies of 2026, verifying the stability of this ice has moved from scientific inquiry to an urgent audit of global security.

"You can’t tweet a drill hole," says Michael Vance. "Washington can argue about models and projections all day. But when you lower a sensor two thousand feet down and it comes back registering water temperatures three degrees above freezing, that is not a model. That is a receipt."

Living on the edge of this catastrophe requires a cognitive dissonance that is hard to sustain. The camp operates on a razor's edge of safety. A sudden storm can ground evacuation flights for weeks, leaving the team isolated in temperatures dropping to minus 40 degrees. They sleep on top of the very thing that threatens to drown their hometowns.

Leaving the Ice

The roar of the Twin Otter’s engines cuts through the silence that has defined the last six weeks for the team at Camp 20. It is a violent intrusion, signaling the end of the vigil. For the glaciologists, the extraction is not just a logistical maneuver; it is an admission of limit. They cannot stay. The Antarctic winter is encroaching, bringing temperatures that would snap steel and freeze hydraulic lines in seconds.

Field technician James Carter (a pseudonym) describes the departure as a "tactical retreat from a losing war." The enemy here is not a foreign power, but physics. The hard drives he guards contain terabytes of seismic data and radar interferometry that confirm what satellites had only hinted at: the grounding line of Thwaites is retreating at a rate that defies previous conservative models.

The disconnect between the ice and the mainland has never been starker. While Washington debates the merits of the "Minneapolis Freeze" disaster relief funds and the viability of new offshore drilling permits, the process initiated here operates on a timeline indifferent to election cycles or quarterly earnings. The researchers are bringing back proof of an irreversible tipping point. A 2025 study by the British Antarctic Survey had already warned that the ice shelf’s disintegration could trigger a cascading collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. The data secured by Carter and his team likely tightens that window, turning a theoretical risk into a tangible liability for every coastal asset from Miami to Manhattan.

As the plane lifts off, banking sharply to avoid the sheer face of the calving front, the camp site is already vanishing, swallowed by the drift. The visual evidence of human presence is erased in minutes. But the vigilance has transferred from the ice to the server rooms of academic institutions, where this data will face its own struggle for survival against skepticism and budget cuts. The scientists are leaving the ice, but the silence they leave behind is deceptive. Beneath the surface, the fracture continues to widen, a silent countdown that will proceed whether we choose to watch it or not. The vigil is over, but the event has only just begun.