Capitalist Capitulation: Venezuela's Desperate Pivot from Bolivarian Ideology to Oil Survival

The Signature That Ended an Era

In a windowless annex of the Miraflores Palace, far removed from the balcony where Hugo Chávez once thundered against the "Yankee empire," the Bolivarian Revolution didn't end with a bang, but with the quiet scratch of a pen. On Thursday morning, acting President Delcy Rodríguez signed the "Organic Law for the Strategic Modernization of the Hydrocarbon Sector," a bureaucratic title that belies its seismic impact. With no televised rallies, no sea of red shirts, and conspicuously absent rhetoric about "sovereignty," the administration effectively dismantled the state monopoly that had defined Venezuelan identity for a quarter-century. The 2026 reforms quietly erase the mandatory 51% stake held by Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) in joint ventures, opening the door for foreign corporations—including American giants—to hold majority operational control for the first time since the nationalization waves of the mid-2000s.

This legislative pivot is not an ideological awakening but a survival mechanism. For two decades, the narrative in Caracas was that Venezuela’s oil was the people’s patrimony, a sacred trust protected from foreign exploitation. However, the economic reality of 2026 has rendered such nationalism an unaffordable luxury. With the Trump administration doubling down on "America First" energy dominance and U.S. shale production keeping global prices tempered despite geopolitical volatility, Venezuela found itself sitting on the world’s largest proven reserves with no capital to extract them. As lead analysts from Houston-based risk consultancies noted in client briefings earlier this week, Caracas finally accepted that 300 billion barrels of oil in the ground are worth zero dollars. They aren't selling the family silver because they want to; they are selling it because the house is foreclosure-bound.

The specific provisions of the law are stark. It authorizes "strategic partners" to assume procurement, hiring, and export capabilities—functions previously jealously guarded by PDVSA. This de facto privatization acknowledges a grim truth documented in recent OPEC reports: Venezuela’s infrastructure has degraded to the point where the state lacks not just the money, but the technical capacity to turn the taps back on. By ceding control, the Maduro-Rodríguez apparatus is betting that tax revenue from Western-run fields will be enough to stabilize a cratering economy, even if it means surrendering the command-and-control economy that was the hallmark of Chavismo.

Terms of Surrender: Royalties and Arbitration

The technical heart of the 2026 Hydrocarbons Law reads less like a piece of sovereign legislation and more like a distressed asset prospectus designed for Houston boardrooms. For two decades, the Bolivarian framework operated on the assumption that access to the world’s largest proven reserves was a privilege for which international oil companies (IOCs) would pay a premium. The new statutory language implicitly admits that this leverage has evaporated. By capping royalties at 30%—down from the confiscatory rates that often exceeded 50% under the previous regime—Caracas is acknowledging that its heavy, sulfur-rich crude is no longer a strategic imperative for the West, but a logistical burden that must be competitively priced against the light, sweet alternatives flooding the market from neighboring Guyana and Brazil.

This fiscal retreat is substantial, but the legal concession is arguably more profound. For years, the "poison pill" for Western investment was Article 22, which mandated that all disputes be settled in Venezuelan courts. The 2026 reform quietly excises this nationalist pillar, explicitly authorizing international arbitration tribunals, such as the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), for joint ventures involving significant foreign capital. Legal experts at major energy firms have long cited the lack of impartial recourse as the primary blockade to deploying fresh capital beyond minimum maintenance levels.

Crucially, the silence of the usually vocal military sector points to a parallel, unwritten agreement. Intelligence reports circulating in Washington suggest that a significant portion of the new revenue streams has been discreetly earmarked for military leadership compensation, ensuring the armed forces remain acquiescent during this ideological U-turn.

Regional Royalty Rates: The Race for Competitiveness (2026)

The necessity of these terms becomes starkly apparent when viewing the regional competitive landscape. While Venezuela clung to resource nationalism, Georgetown and Brasília were rewriting the playbook on attracting upstream investment. Guyana’s production sharing agreements created an oil boom that left Venezuela's crumbling infrastructure in the dust. The 30% royalty cap is a direct attempt to narrow the fiscal gap, signaling to the market that the risk premium of operating in the Orinoco Belt is finally being offset by favorable fiscal terms.

Washington's Invisible Hand

The silence in the halls of the Miraflores Palace is no longer filled with the fiery rhetoric of Bolivarian socialism, but rather the quiet, clinical scratching of pens drafting the 2026 Hydrocarbons Law. This legislative pivot is widely viewed by Houston-based energy analysts and Washington policy circles not as a local innovation, but as a carefully choreographed capitulation. The timing is far from coincidental. As the Trump administration accelerates its "America First" deregulation agenda, the sudden liberalization of Venezuela’s oil sector suggests that the "Invisible Hand" of Washington has been busy in the shadows, crafting a deal that trades ideological purity for economic life support.

For senior consultants monitoring the region, the document reads less like a sovereign decree and more like a term sheet from a US State Department briefing. The law’s most radical provision—allowing foreign entities to hold up to 80% equity in joint ventures and granting them full operational control—mirrors long-standing demands from the American petroleum lobby. By stripping the state-run PDVSA of its mandatory majority stake, Caracas is effectively privatizing the "crown jewels" of the revolution to ensure the flow of USD ($) resumes before the global shift toward renewables renders their heavy crude reserves obsolete.

Rumors of a "Houston-Caracas Corridor" have intensified in recent weeks, following reports of high-level, back-channel meetings in Mexico City between Venezuelan technocrats and representatives from the US Treasury. These discussions likely paved the way for the recent easing of Treasury Department licenses, which now permit expanded drilling operations for US majors. The trade-off is stark: Venezuela receives a reprieve from the crushing weight of sanctions and a desperate injection of capital, while the US secures a nearby, stable source of heavy crude to offset the volatility caused by the administration’s aggressive stance toward Middle Eastern imports and the ongoing isolation of Moscow.

Projected Venezuelan Oil Output Recovery Following 2026 Privatization (Source: IEA and EIA Projections)

Critics of this "shadow deal" argue that the US is essentially rewarding a regime it once labeled a pariah, prioritizing market stability and resource security over the promotion of democratic institutions. From this perspective, the 2026 law is a victory for corporate interests that have successfully lobbied the White House to view Venezuela through the lens of a commercial opportunity rather than a geopolitical threat. However, proponents within the administration suggest that integrating Venezuela back into the global free market is the most effective way to dilute the influence of rival powers like China and Iran in the Western Hemisphere.

For local economists observing the shift, the debate over sovereignty is secondary to the need for basic services. While the 2026 law may be "pre-written" by foreign interests, it offers a tangible path toward stabilizing the local currency and potentially curbing the hyperinflation that has defined the last decade. Yet, there remains a deep-seated anxiety that by opening the floodgates to foreign capital under such lopsided terms, the nation is merely trading one form of dependency for another.

The 2026 Reality: When Ideology Meets Bankruptcy

For the architects of the Bolivarian Revolution, the irony is as thick as the heavy crude sitting beneath the Orinoco Belt. After two decades of rhetorical war against "imperialist extraction," the administration in Caracas has effectively hung a "For Sale" sign on the world's largest proven oil reserves. The 2026 Hydrocarbons Law is not a policy update; it is a bankruptcy proceeding disguised as legislation. With hyperinflation still ghosting the economy and infrastructure crumbling after years of neglect, the state-owned PDVSA has ceased to be an engine of sovereignty and has become a liability that the state can no longer subsidize.

The arithmetic of this surrender is brutal but undeniable. In a global market accelerating toward decarbonization—despite the Trump administration's rollback of domestic green mandates—time is the one resource Venezuela does not have. Every barrel left underground today risks becoming a "stranded asset" by 2035. Veterans of Latin American energy markets note the shift in tone during recent closed-door roadshows in Texas. Three years ago, the conversation was about "sovereignty" and "majority control." Now, it’s about "operational autonomy" for foreign partners. They know that without Western capital and, more importantly, Western technology to process that heavy crude, their national treasure is worth zero.

The Efficiency Gap: Cost of Extraction vs. Production (2020-2026)

As the chart illustrates, while production has seen a modest uptick due to limited easing of restrictions, the cost per barrel for PDVSA to extract its own oil has skyrocketed due to dilapidated infrastructure and brain drain. The 2026 law is an admission that the state can no longer afford to be in the oil business as an operator; it can only afford to be a landlord, collecting rent while foreign majors do the actual work of salvaging the economy.

The Fragility of the 'Acting' Seal

The ink on the 2026 Hydrocarbons Law was barely dry before legal teams in Houston and New York began dissecting its most dangerous flaw: the constitutional validity of the signature at the bottom. While the administration in Caracas markets this legislative overhaul as a permanent bridge to Western capital, constitutional scholars and risk analysts warn it may be little more than a pier built on quicksand. The central anxiety for US investors is not the geology—Venezuela’s reserves remain the largest in the world—but the "Acting" or disputed nature of the executive authority granting these concessions in the chaotic political landscape of early 2026.

For legal experts advising mid-sized exploration firms, the arithmetic is terrifyingly simple yet legally paralyzed. While the fiscal terms are undeniably attractive—offering tax holidays and operational autonomy unseen since the pre-Chavez era—the "sovereign guarantee" is virtually worthless if the administration itself is deemed transitional or illegitimate by future courts. The fear is not just expropriation, the classic risk of the Bolivarian era, but nullification. If the current power structure fractures or yields to a transition government, contracts signed under the distress of 2026 could be voided on the grounds that the signatories lacked the constitutional authority to alienate national resources.

Caracas vs. The Countryside: Who Benefits?

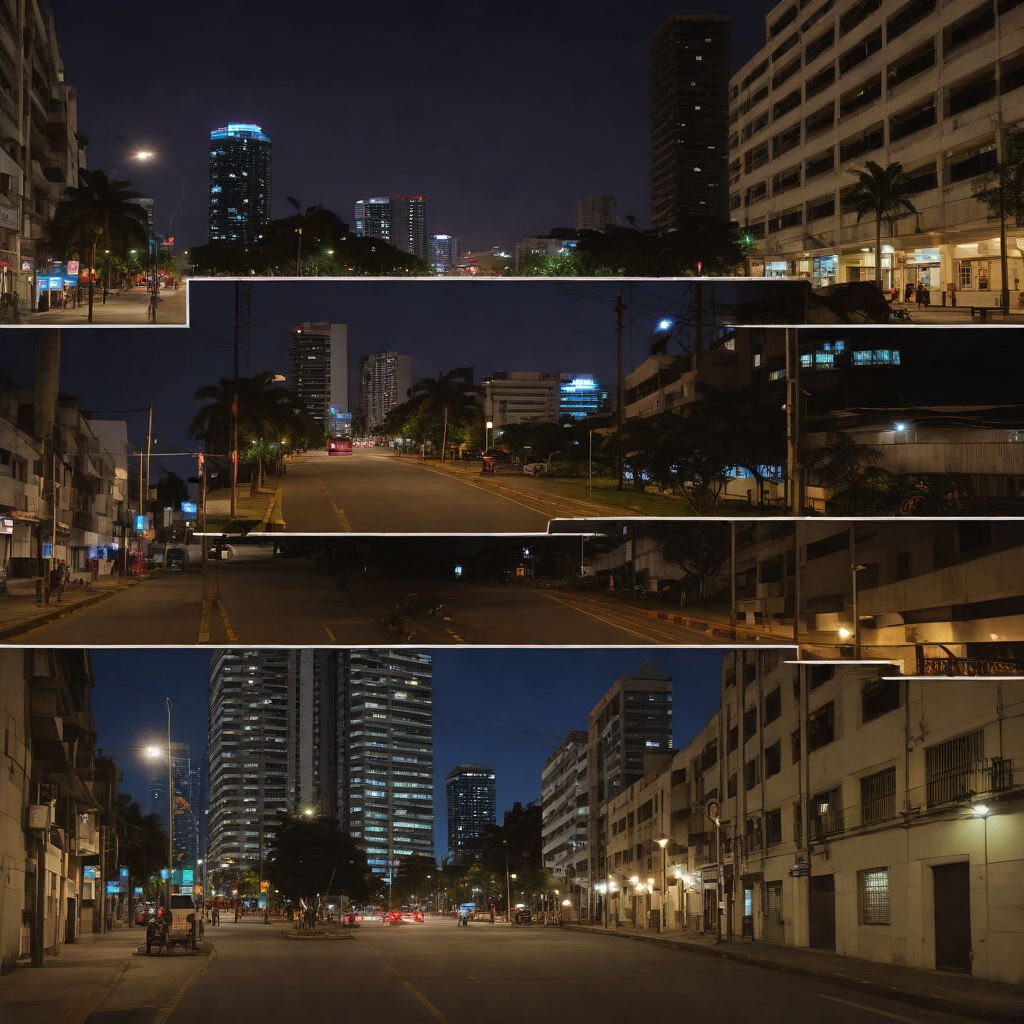

The gleaming towers of Las Mercedes, Caracas’s financial district, tell one story. Here, in what locals call "The Bubble," the impact of the 2026 Hydrocarbons Law is already visible in the fleet of armored Toyota 4Runners lining the streets and the influx of American and European energy consultants filling the Marriott. The law, effectively dismantling the late Hugo Chávez’s 2001 mandate of state majority control, has been welcomed by Wall Street and the Trump administration as the only viable path to solvency. Yet, travel four hundred miles west to Maracaibo, once the proud heart of the petroleum industry, and the narrative fractures.

For millions of Venezuelans living outside the capital's fortified enclaves, the "privatization of survival" has not brought the promised trickle-down prosperity; it has only solidified a brutal two-tier reality. The new legal framework guarantees foreign partners operational autonomy—meaning they can generate their own power, import their own supplies, and secure their own perimeters. While this ensures that Chevron and Eni can pump crude efficiently, it effectively decouples the oil industry from the crumbling national grid that the rest of the country relies on.

Residents in Zulia state describe the disconnect with bitter clarity. While the flares of the joint-venture refineries burn bright on the horizon, their neighborhoods remain dark, often going 30 hours without electricity. They argue that a country within a country is being built—one part for the oil and the foreigners, the other for the locals to wait in line.

The Divergence: Oil Exports vs. Public Spending Index (2022-2026)

A New Blueprint for Rogue States?

The 2026 Hydrocarbons Law is not merely a legislative update; it is the white flag of a failed ideological experiment. By effectively dismantling the state's monopoly on its subsoil, the Caracas regime has admitted that the "Bolivarian Dream" cannot survive the cold reality of a world where energy demand is increasingly bifurcated between high-efficiency AGI-managed grids and a US-led oil market defined by aggressive deregulation. For Washington, this pivot serves as a validation of the "America First" doctrine, which leverages economic isolation and technological supremacy to force ideological foes into market-driven submission. As the second Trump administration accelerates domestic shale production through the 2025-2026 "Drill-to-Dominate" executive orders, the global window for high-cost, state-run oil is slamming shut.

Strategists at leading Dallas-based energy funds view the new law as a "fire sale" rather than a sovereign partnership. The risk premium for Venezuelan assets remains astronomical, but the potential for 100% private control of upstream assets is a siren song that capital-starved regimes have historically resisted until the very end. The 14% uptick in preliminary letters of intent from US-led consortiums following the law’s passage signals a broader trend: in the 2026 landscape, where AI-optimized extraction in the Permian Basin has made the US the global price-setter, rogue states can no longer afford the "luxury" of nationalized inefficiency.

Venezuela Oil Investment Shift: State vs. Private Projections (Source: 2026 Latin American Energy Review)

The global implication of this capitulation suggests a new, harsher blueprint for international relations in the mid-2020s. If the world’s largest oil reserves are essentially being "re-marketized" under the pressure of a US-led economic blockade and technological obsolescence, the "Rogue State" model of autarky is effectively dead. Regimes in Tehran or even Pyongyang may be watching Caracas as a case study in "Managed Surrender": can a state retain its authoritarian political structure while surrendering its economic soul to the very market forces it once cursed? The Venezuelan case suggests that while physical borders are becoming more rigid under current global trade wars, the flow of capital and the relentless pace of technological displacement are forces no regime can truly withstand for long.