The Celadon Strategy: How Samsung's Art Collection Outflanked Washington Politics

The Quiet Blockbuster on the Mall

The wind whipping off the Potomac this final week of January has been merciless, carrying with it the bitter chill of the "Minneapolis Freeze" that has dominated national headlines. Yet, on the National Mall, a curious phenomenon has defied the sub-freezing temperatures and the prevailing mood of national anxiety. Outside the National Museum of Asian Art, a line snakes down Independence Avenue—not for a rally or a protest, but for a glimpse of porcelain.

While the 119th Congress remains deadlocked over President Trump’s latest deregulation executive orders and the drone warfare budget, Washington’s weary populace has found an unlikely sanctuary in the "Korean Treasures" exhibition. This is the collection of the late Samsung Chairman Lee Kun-hee, a hoard so vast and culturally significant that its donation to the South Korean state was dubbed the "donation of the century." Its arrival in the U.S. capital was expected to draw the usual diplomatic circles and art historians. Instead, it has become a quiet blockbuster, drawing crowds that rival the wildest days of the "Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors" craze, but with a markedly different energy.

There are no selfie sticks here, and the hushed reverence inside the galleries stands in stark contrast to the transactional noise of the current administration’s "America First" trade rhetoric.

For James Carter, a 42-year-old lobbyist specializing in energy policy, the exhibition offers a rare pause in a month defined by labor strikes and algorithmic market volatility. "My day is usually measured in 15-minute intervals and stock tickers," Carter says, standing before a 17th-century white porcelain moon jar. "You look at this jar—it’s imperfect, it’s asymmetrical, but it feels more complete than anything I’ve read in a policy briefing this year. It forces you to slow down."

Carter’s sentiment reflects a broader shift in how American audiences are engaging with Korea. For the better part of the last decade, the cultural exchange was dominated by the kinetic energy of K-Pop and the dark, violent critiques of K-Drama. It was loud, colorful, and often consumed through the glowing rectangles of smartphones. The success of the Lee collection suggests a maturation of this relationship. Visitors are not looking for the next dopamine hit; they are engaging with the Joseon Dynasty’s Confucian austerity and the meditative void of monochrome painting.

Smithsonian curators note that the demographic mix is unprecedented. It is not merely the K-Wave fandom aging up. It is the "NPR crowd," the policy wonks, and the tourists who might typically prioritize the Air and Space Museum. Data from the museum’s opening month indicates a retention time—the duration a visitor spends in the gallery—nearly double the average for special exhibitions.

Average Visitor Dwell Time: Major D.C. Exhibitions (Jan 2026)

This "quiet" engagement signals a disconnect between the geopolitical narrative and the cultural reality. On Capitol Hill, South Korea is discussed primarily as a strategic node in the semiconductor wars—a "chip fab" ally whose value is calculated in nanometers and yield rates. Yet, a few blocks away, Americans are entranced not by Korea’s silicon wafers, but by its celadon. The exhibition implicitly argues that a nation capable of producing such profound aesthetic philosophy is not merely a manufacturing hub or a junior military partner, but a civilization of equal weight.

The Semiconductor King's Secret Garden

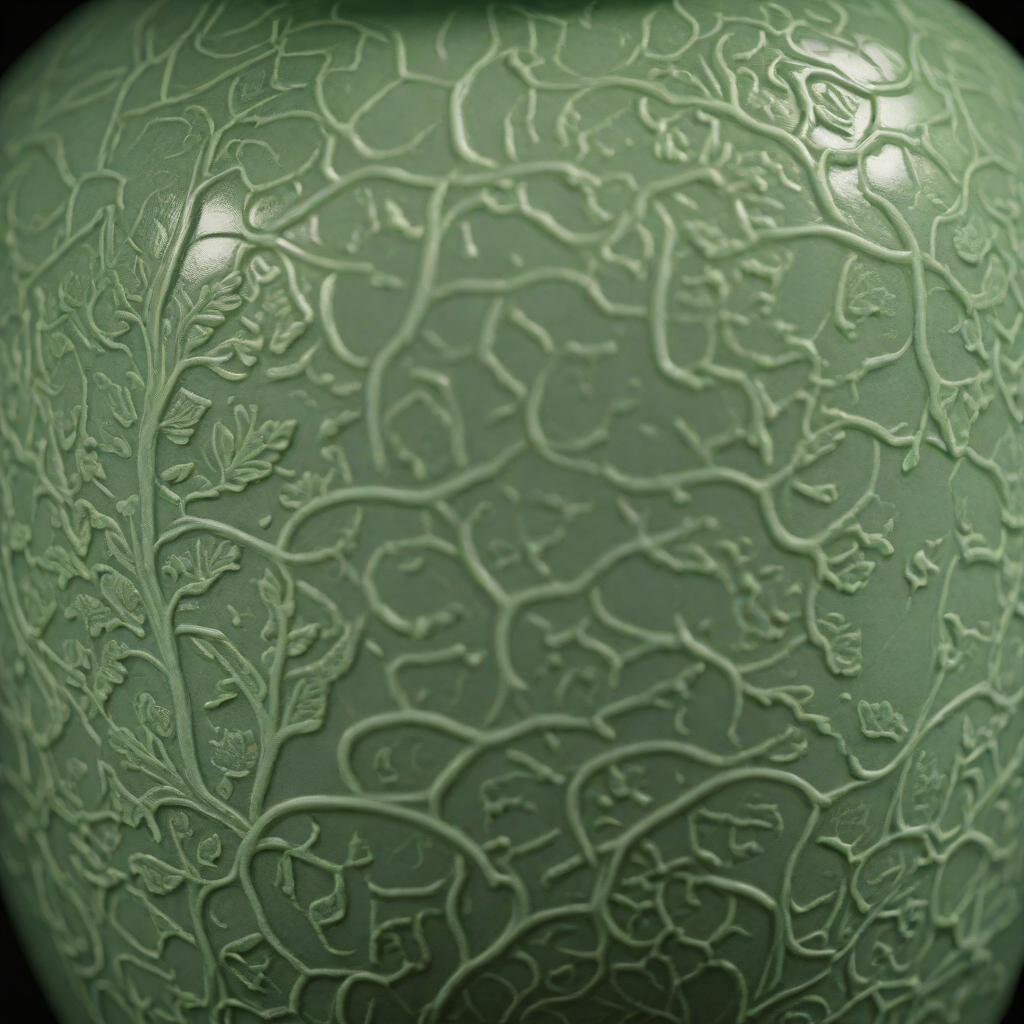

In the hushed, climate-controlled galleries of the National Museum of Asian Art, visitors are confronting a side of South Korea that contradicts the flashing neon of K-Pop and the sterile precision of silicon wafers. The "Korean Treasures" exhibition—a diplomatic blockbuster amid the tense trade atmosphere of 2026—showcases porcelain so sublime it seems to defy gravity. Yet, the man behind this accumulation of beauty was better known for a different kind of rigor. Lee Kun-hee, the late Chairman of Samsung, was the architect of the digital fortress that now sits at the center of President Trump’s supply chain strategies. Unknown to many Western policymakers who view Samsung merely as a geopolitical chess piece, the industrialist who demanded absolute zero-defect manufacturing in memory chips applied an even more fervent, almost manic, obsession to the acquisition of culture.

To understand the collection, one must first dismantle the caricature of the "Samsung Man." In the business world, Lee was a Darwinian figure, feared for his silence and his sudden, sweeping decrees. His 1993 "Frankfurt Declaration"—where he famously ordered executives to "change everything except your wife and children"—transformed Samsung from a second-tier appliance maker into a global hegemon. He once ordered a bonfire of 150,000 defective phones in a factory courtyard to instill a culture of quality. This was the "Silicon" Lee: cold, calculating, and obsessed with overtaking Japanese rivals like Sony. But while his engineers were battling to shrink nanometers in Suwon, Lee was quietly constructing a "Secret Garden" that would eventually rival the holdings of the Guggenheim or the Tate.

Lee’s approach to art was not merely aesthetic; it was an act of national defense. For decades, whenever a rare piece of Korean heritage—a 14th-century Goryeo Buddhist painting or a Joseon-era white porcelain jar—surfaced in a Japanese auction house or a private American collection, Lee was often the invisible hand ensuring its repatriation. He treated cultural heritage with the same strategic gravity as semiconductor IP. A 2025 retrospective analysis by the Wall Street Journal noted that Lee’s acquisition strategy mirrored his corporate strategy: identify the undervalued asset, acquire it aggressively, and wait for the world to catch up to its value. He recognized early that for a nation to command true respect on the global stage, it needed to export more than just Galaxy phones; it had to export its soul.

Beyond the K-Pop Echo Chamber

For nearly a decade, the American perception of Korean culture was dominated by a neon-soaked, algorithm-friendly aesthetic. It was the era of "Hallyu 2.0"—defined by the synchronized precision of BTS and the dystopian candy-gore of Squid Game. These exports were phenomenally successful, generating billions in revenue and capturing the imagination of Gen Z. However, they possessed the volatility inherent to pop culture: rapid obsolescence. A chart-topping hit lasts weeks; a 12th-century celadon incense burner lasts millennia. The arrival of the "Korean Treasures" exhibition in Washington marks a pivotal shift from this ephemeral consumption to institutional canonization, suggesting that Seoul is no longer just a content factory for the American masses, but a civilizational peer to the West.

The distinction is critical in the current geopolitical climate. Under the Trump administration’s "America First" doctrine, trade relationships are increasingly transactional, scrutinized through the harsh lens of deficits and supply chain security. Semiconductors and EV batteries—the hard power assets—are often sources of friction, subject to tariffs and negotiation. In contrast, high art operates above the fray of trade wars. When the late Samsung Chairman Lee Kun-hee’s collection filled the halls of the National Museum of Asian Art, it did not ask for market access; it demanded historical reverence.

Shift in US Cultural Imports from Korea (2020-2025)

This pivot to "high culture" serves a strategic function that pop music cannot. It attracts a different demographic—the policymakers, the philanthropists, and the power brokers of D.C., rather than just the teenagers of TikTok. James Carter, the lobbyist and longtime donor to the Smithsonian, noted during the gala opening that his previous exposure to Korea was limited to "business trips to Suwon and my daughter’s Spotify playlist." Standing before the Inwang Jesaekdo (Clearing After Rain in Mt. Inwang), a masterpiece of Joseon dynasty landscape painting, Carter admitted, "This forces you to reckon with a depth of history that a smartphone screen just can't convey. It changes the conversation from 'what can you build for us' to 'who are you'."

Diplomacy by Other Means

While the Trump administration’s 2026 trade agenda emphasizes a "reciprocal" approach—often translating to aggressive tariffs on foreign-made electronics and automobiles—the Korean Treasures exhibition has emerged as an unlikely geopolitical stabilizer. In the hushed halls of the National Gallery of Art, the tension of the Oval Office feels worlds away, yet the objects on display are doing the heavy lifting of statecraft. Sarah Miller, a legislative aide who frequently navigates the friction of the House Ways and Means Committee, notes that the exhibition allows visitors to encounter a civilization that has as much to teach the West about longevity as it does about logic gates.

This shift in perception is not merely anecdotal; it represents a strategic pivot in Seoul’s engagement with Washington. As the US leans into an isolationist "America First" posture, the traditional pillars of the alliance—military interdependence and supply chain integration—are being stress-tested by a White House that views all international relationships through a transactional lens. By showcasing the depth of its aesthetic history through the massive collection formerly held by the late Samsung chairman, Korea is asserting a status that cannot be quantified by a trade deficit. This "artistic shield" creates a cultural buffer that makes the political cost of economic decoupling significantly higher for American lawmakers.

Growth in US 'Cultural Affinity' Index Toward South Korea (Source: Atlantic Council/Pew Research 2026 Projection)

The Burden of Corporate Heritage

The "Lee Kun-hee Collection" arrived in Washington not merely as a cultural envoy, but as the final, gilded chapter of a deeply complex corporate succession saga. For the American visitor walking through the quiet galleries of the National Museum of Asian Art, the backstory is often obscured by the aesthetic brilliance. Yet, to view these artifacts purely as objects of beauty is to ignore the industrial brutality and dynastic maneuvering that preserved them. This exhibition represents a historic settlement—both literal and figurative—between South Korea’s most powerful chaebol and its society, a transaction that now echoes in the halls of American power.

The provenance of this collection is inextricably linked to the death of Chairman Lee Kun-hee in 2020 and the subsequent staggering inheritance tax bill faced by his heirs—a figure exceeding 12 trillion won (approximately $9 billion USD). In a move that stunned both the art world and tax regulators, the family donated some 23,000 works to the Korean state. Miller, the legislative aide, described it as "the most sophisticated feat of reputation management in modern corporate history." She argues that while the donation did not directly offset the tax bill in a dollar-for-dollar deduction sense under Korean law, it purchased something far more valuable: a shift in the national narrative.

This dynamic is hardly foreign to the American observer. The trajectory from industrial titan to cultural benefactor is a well-worn path in the United States, paved by figures like Frick, Carnegie, and Mellon, whose names now adorn the very institutions that define American high culture. The "Samsung Titan" is, in many ways, the 21st-century equivalent of America’s Gilded Age robber barons, seeking immortality not through steel or semiconductors, but through the soft power of art. However, the reception in Washington in 2026 adds a distinct geopolitical layer. In an era where the Trump administration prioritizes "America First" and trade barriers are rising, high art remains one of the few porous borders.

A New Permanent Address for Korean Culture

The wrapping comes off the crates, and the shipping manifests are signed, but the institutional hangover from the "Lee Kun-hee Collection" exhibition suggests something far more durable than a traveling blockbuster. For decades, American engagement with Korean culture has been bifurcated: the utilitarian consumption of its semiconductors and the ephemeral consumption of its pop culture. However, the sheer gravity of the Samsung patriarch's collection has forced a structural recalibration within America’s cultural institutions, transitioning Korean art from a seasonal curiosity to a permanent tenant on the National Mall and beyond.

While K-Pop concerts generate transient revenue, museum wings generate canon. We are witnessing a pivot reminiscent of the 1980s "Japonisme" revival, where economic dominance translated into high-cultural legitimacy. This time, however, the capital flow is reversed. It is not American collectors plundering exotic goods, but Korean corporate patronage—led by Samsung and Hyundai—funding the very walls that house their heritage.

Growth in US Museum Endowments for Korean Art (2022-2026)

The "Korean Treasures" exhibition has effectively ended the era where Korea was viewed solely as a manufacturer of the future—chips and batteries—or a manufacturer of entertainment. It has staked a claim on the past. By placing a moon jar next to a Grecian urn or a Renaissance bronze, the collection asserts an equality of civilization that catchy pop choruses never could. The celadon has arrived, and unlike the silicon that cycles out every eighteen months, it intends to stay.