The Seoul Shock: How US Protectionism Is Stifling a Key Ally

The Canary Falls Silent

For decades, global economists have monitored the pulse of South Korea—the world's premier bellwether for trade health—to forecast the direction of the global economy. Often termed the "canary in the coal mine," Seoul’s export-driven engine typically sputters months before a recession hits New York or London. This week, that canary didn't just stumble; it fell silent. In a release that has sent shockwaves through Wall Street and Washington alike, Statistics Korea confirmed that industrial growth has decelerated to a stagnant 0.5%, the lowest figure recorded since the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

This near-halt stands in stark contrast to the optimism of just two years ago. In 2024, the nation posted a robust 2.8% growth rate, fueled by an AI semiconductor boom that many hoped would immunize the Pacific Rim against geopolitical friction. That hope has now evaporated. The plunge from 2.8% to 0.5% is not merely a statistical correction; it is the arithmetic of a broken promise. It signals that the "Trump 2.0" doctrine of aggressive protectionism—tariffs, export controls, and the forced reshoring of supply chains—is no longer just a political talking point. It is a kinetic force that is actively dismantling the export models of America’s closest strategic allies.

The gravity of this downturn cannot be overstated. We are witnessing the first concrete casualty of the new isolationism: a stagnation that exceeds even the volatility of the post-inflationary adjustments seen in 2022 and 2023. By suffocating the flow of intermediate goods—the chips, screens, and batteries that power American consumption—Washington’s policies may have inadvertently triggered a supply shock that will boomerang back to the US consumer in the form of higher prices and scarcity.

South Korea Industrial Growth Rate: The 2026 Deceleration

For the American observer, the temptation is to view this as a distant Asian crisis. That would be a fatal miscalculation. The 0.5% figure is not just a Korean metric; it is a leading indicator for the US tech sector, which relies heavily on the very supply chains now grinding to a halt. If the "America First" wall keeps out the competition, it also seemingly locks out the essential vitality of global commerce, leaving the US economy to face the specter of stagflation alone.

Anatomy of the 'Seoul Shock'

The number that flashed across trading terminals on Wall Street this morning—0.5%—was not just a statistic; it was a siren. Today, the global economy's canary is gasping for air, and the hands tightening the grip are not in Beijing or Pyongyang, but in Washington.

The pain is most acute in the sectors that bind the US and Korean economies together: semiconductors and automobiles. For Michael Johnson, a procurement strategist for a major US consumer electronics firm, the "Seoul Shock" is already manifesting in supply chain turbulence. "We are seeing a hesitation to commit to long-term contracts from our Korean partners," Johnson notes. "They are terrified that a new executive order from the White House could render their US-bound exports uncompetitive overnight. It’s not a supply shortage; it’s a certainty shortage."

This hesitation is creating friction in the supply chain that ultimately translates to higher prices for American consumers. The dismantling of the predictable free-trade consensus has hit the semiconductor industry particularly hard. South Korean chipmakers, squeezed between US restrictions on Chinese exports and demanding new "guardrails" for US market access, are facing an existential squeeze. The 0.5% figure reflects a broader dismantling of the export-led growth model that Washington itself championed for seventy years. By forcing allies to choose between economic suicide and geopolitical compliance without offering a safety net, the US risks weakening the very industrial base it relies on to counter China’s technological ascent.

South Korea GDP Growth Rate (Year-over-Year)

The Price of 'America First'

The rhetoric of "America First" was sold to the Rust Belt as a shield—a necessary fortification to rebuild domestic industry. Yet, in the boardrooms of Seoul and the manufacturing hubs of Ulsan, this shield is being felt as a suffocating tariff wall. For Lee Jun-ho, who manages a precision electronics firm in Gumi that supplies components to US-based EV manufacturers, the policy shift has been catastrophic. "We were told to decouple from China and invest in the US alliance," Lee explains, noting that his operating margins have evaporated under new import levies. "Now, we are blocked from the Chinese market by security restrictions and priced out of the US market by tariffs. We are trapped on an island."

This stagnation in South Korea is a flashing red light for the US economy itself. The prevailing wisdom in Washington assumes that foreign pain will translate into domestic gain, but the interconnected nature of modern semiconductor and battery supply chains suggests a different outcome: a "boomerang" effect. As Korean manufacturers scale back production to survive the 0.5% growth reality, US assembly lines waiting for those high-tech inputs face delays and price hikes. The contraction abroad is a precursor to supply shocks at home, threatening to drag the American market into a stagflationary spiral where consumer prices rise even as industrial output slows.

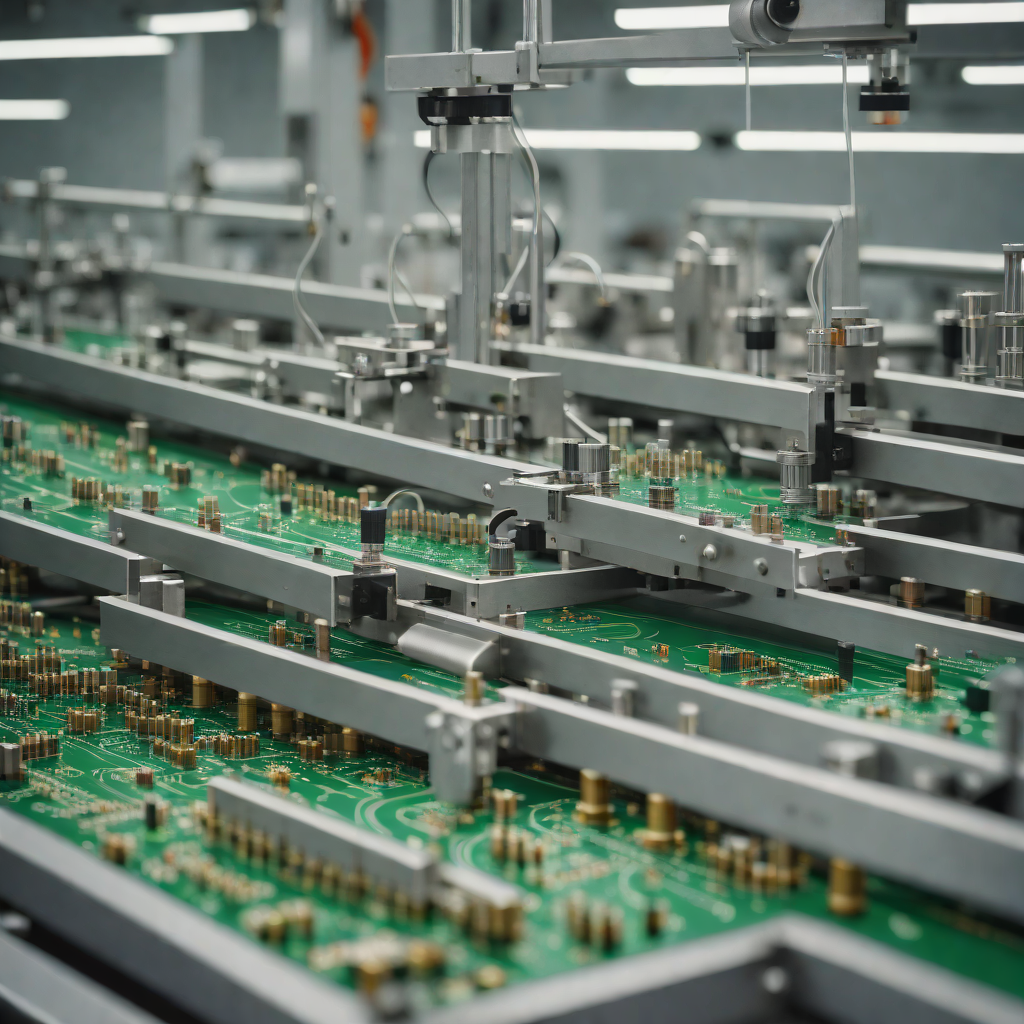

The Adjustment Crisis: Machines Over Men

Beneath the macroeconomic headline lies a more disturbing trend: a phenomenon economists are calling "jobless stagnation," where industrial output effectively decouples from human employment. In the sprawling industrial complexes of Ulsan, the heart of Korea’s manufacturing prowess, the slowdown looks different than previous recessions. Typically, a drop in demand leads to idle machinery and silent assembly lines. Today, the lines are moving, but the human workforce is vanishing.

For Park Ji-hoon, a 45-year-old production manager at a mid-sized automotive components supplier, the reality of this "Adjustment Crisis" is visible in the empty lockers of his breakroom. "Five years ago, a slowdown meant we cut shifts," Park says, gesturing to a floor now dominated by high-speed robotic arms. "Now, we cut people to afford the machines. The new US tariff structures mean we cannot compete on price if we pay human wages. We have to automate to survive the American market."

This is the hidden cost of the "America First" protectionist pivot. By erecting high tariff walls, the Trump administration has forced allies like South Korea into a corner. To jump over the tariff barrier and maintain their razor-thin margins in the US market, Korean firms are aggressively shedding labor costs—not by moving factories to cheaper jurisdictions, which risks further US ire, but by replacing workers with capital-intensive automation.

South Korea GDP Growth vs. Industrial Robot Density (2020-2025)

Stagflation's Shadow

The definitive signal arrived not from a Federal Reserve press release, but from a somber report out of the Ministry of Economy and Finance in Seoul. For US policymakers, the data presents a paradox that clashes with the prevailing narrative of the Trump administration’s second term. While the White House champions tariffs as a tool for re-industrialization, the "Seoul Warning" suggests these measures are effectively importing stagnation.

The logic is brutal but simple: South Korea acts as a primary processor for the global tech ecosystem, turning raw materials into the intermediate goods that American factories finish. When Seoul’s output falls to 0.5%, it indicates that the cost of moving these goods across the Pacific—now burdened by aggressive levies and regulatory friction—has become prohibitive. The macroeconomic implication is the specter of stagflation—the toxic combination of stagnant growth and rising prices—returning to the global stage. If the 0.5% contraction in Seoul is indeed the canary in the coal mine, the recoil on the American economy will likely arrive not as a sudden crash, but as a persistent, grinding erosion of purchasing power, where goods become more expensive even as the engines of global commerce cool.